Agnes M. Burns

Curriculum Specialist, Brookfield, CT

Introduction

Since the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002, America’s public schools have been challenged to demonstrate “…the four principles of President George W. Bush’s education reform plan: stronger accountability for results, expanded flexibility and local control, expanded options for parents, and an emphasis on teaching methods that have been proven to work” (U.S. Department of Education, 2003). As many classroom teachers and administrators anxiously await scores which prove that adequate yearly progress in reading, writing, and mathematics has been achieved, they are also looking ahead at what they can do to further improve scores especially in those populations that traditionally perform below the expected levels.

Incremental gains have been established so that by the year 2014 all children will, ideally, be reading at the proficient level by the end of third grade. Despite the aggressive intentions of legislators, international, national, and state-mandated testing has consistently shown several gaps in literacy achievement. There is one subgroup that has unexpectedly emerged: boys. Classroom teachers and researchers are aggressively searching for answers on how to address the gender gap in literacy.

As Freedmon pointed out “Gendered results on high-stakes testing will require a thoughtful response from school districts. Additional research is required” (Freedmon, 2003, p. 11). This paper will report on how choice of reading topics impacted a small group of fourth-grade boys. The results from this small study may impact only a small community, but it is a start.

The statistics that reflect what is happening in our classrooms and our world include these from an article titled “The Trouble with Boys,” written by Peg Tyre, in Newsweek magazine’s January 30, 2006 issue:

- Girls ages 3 to 5 are 5% more likely than boys to be read to at home at least three times a week.

- Girls are 10% more likely than boys to recognize words by sight by the spring of first grade.

- Boys ages 5 to 12 are 60% more likely than girls to have repeated at least one grade.

- Girls’ reading scores improve 6% more than boys’ between kindergarten and third grade.

- First- to fifth- grade boys are more likely than girls to have disabilities such as emotional disturbances, learning problems or speech impediments.

- Fourth-grade girls score 3% higher on standardized reading tests than boys.

- Fourth-grade girls score 12% higher on writing tests then boys. (p. 47)

These statistics are from the U.S. Department of Education, Centers for Disease Control.

Later, in the same article, Margaret Spellings, U.S. Secretary of Education, states: “This widening achievement gap has profound implications for the economy, society, families and democracy” (Tyre, 2006 p.46). What has been happening in our classrooms is that as a child moves up from grade to grade, those who are struggling face increasingly more difficult curriculum. The skills needed to decode and comprehend text literally and more importantly, inferentially and critically, are dependent on so many factors including prior knowledge of phonics, vocabulary and grammar. If these skills are not developed at an early age, frustration can set in and inevitably, self-esteem plummets.

Major Research Theories

There are two major theories that attempt to account for the literacy gap in boys. One of them is called the Social Constructivist Theory. Smith and Wilhelm (2002) advocate that social contexts influence how boys perform. They condensed the flow theory of psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and applied it to boys’ literacy developing these four concepts:

- A sense of control and competence,

- A challenge that requires an appropriate level of skill,

- Clear goals and feedback, and,

- A focus on the immediate experience.

Boys want to be in charge and they want others to see them as capable. They don’t want a task that is too difficult, because they will not be able to complete it and will loose their strong and capable image. They want to know how they are doing – now. As long as a clear description of an appropriate task is given, boys will attempt to complete it. They want the learning to relate to their lives at this time, not some far distant future. They live and learn in the here and now.

The other school of thought, Biological Determinism, is based on the work of Michael Gurian, Kelly King, and Kathy Stevens (2005, 2006). They believe that boys’ brains are “hardwired” differently than girls’ brains. They illustrate this through electronic images of brains. Their observances and interviews have led them to discover more than one hundred structural differences between male and female brains. One of their important conclusions is that boys’ brains have more developed spatial-mechanical functioning, while girls’ brains emphasize verbal-emotive processing. Another interesting finding is that there is less cross-hemisphere communication in boys’ minds and therefore, they experience difficulty in multi-tasking.

Although these two theories differ in how to explain the learning differences between the genders, they share many of the same implications for classroom teachers.

The Purpose of the Statement

This study will attempt to explore elementary-school age male participant performance in literacy when given a choice of topic, a consistently mentioned, significant factor in many studies to date.

Statement of Hypothesis

Hypothesis 1: It was hypothesized that there is a correlation between choice of reading topic and the motivation and engagement of male fourth-grade students.

Corollary to this hypothesis are two subordinate hypotheses:

Subordinate Hypothesis 1: It was hypothesized that boys would favor websites and discussion during their literacy learning.

Subordinate Hypothesis 2: It was further hypothesized that due to their competitive nature, the boys will want to “move up in rank” to demonstrate the successful completion of a task.

Methodology

Participants

The participants were seven fourth-grade boys enrolled at an urban, public school in Torrington, Connecticut where I teach. They were a convenience and purposive sample. The boys ranged in age from nine years and seven months to eleven years and five months. They were available to meet at a mutually available time and all were interested in the topic of World War II. None of the boys had issues that interfered with their learning, such as special education or second language concerns; however, they were a heterogeneous group. Of the seven boys, one was African-American, one was Hispanic, and the others were White.

Several boys had approached me about doing a group focused on World War II. They were available on Friday afternoons from 2:30 to 3:00 while other students are out for chorus. After meeting with a small group and determining their deep interest about this topic, I agreed to arrange for a special reading club called the Forbes’ Flying Tigers. (Forbes is the name of our school and the Flying Tigers was a group of American mercenaries who went to Burma in order to protect the Burma Road, which allowed supplies to reach China during World War II.) Our club meetings started in mid-April and ran through the end of the school year. We actually held our meetings twice a week to accommodate the boys’ desire to learn more about World War II. The second meeting time was during a lunch period. Many literacy activities were done during this period including the necessary testing, a written response assignment, website investigations, and literature circle discussions. I outlined a variety of activities to use for observation and note taking. Each boy received a folder to store materials, a camouflage pencil, and a rank sheet. We planned a culminating activity for the end of the year, which was our Pearl Harbor Wax Museum. At the end of the year, I distributed a questionnaire to the students and their parents, which provided additional feedback.

The classroom teachers indicated that this group of boys was underperforming. They did not appear to be motivated and engaged during the literacy block, especially in the area of writing.

Although I am aware of other factors that might have influenced the results in this study, I carefully considered several such as age, DRA (Developmental Reading Assessment) levels, and their classroom environment and determined that they had no influence over my findings.

Instrumentation-Quantitative

Several means of collecting data were used. A Degrees of Reading Power Test (DRP) was given to assess comprehension. The Degrees of Reading Power (DRP Test) was chosen as one of the quantitative instruments for this research study. It was chosen, in part, because of its ease of administration and familiarity to the participants. The DRP is one of the assessments used in the Connecticut Mastery Test battery. In addition, it is widely accepted as a means of assessing students’ comprehension. The forms used for this study were the J-8 and J-7. Scoring was done manually by the researcher and will be reported as raw scores, DRP units, and percentile. These scores will be compared to the Connecticut Mastery DRP results from spring, 2006. In addition, as a baseline, Connecticut Mastery Scores from 2006 were used.

Results from administering the MARSI – Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory – were compared to the results from The DRP. A correlation between the results from the MARSI will be attempted to determine if there is a relationship between performances on the DRP.

Instrumentation-Qualitative

Qualitative measures include: anecdotal notes, observations, questionnaires for students and parents, and a written response piece. Conversations with classroom teachers, and a variety of assignments given during data collection also were considered.

Anecdotal notes, observations, and teacher input will be maintained to record comments for the purpose of determining levels of motivation and engagement as well as attendance and whether assignments were completed and the quality of the work.

Results

Instrumentation-Quantitative

Quantitative

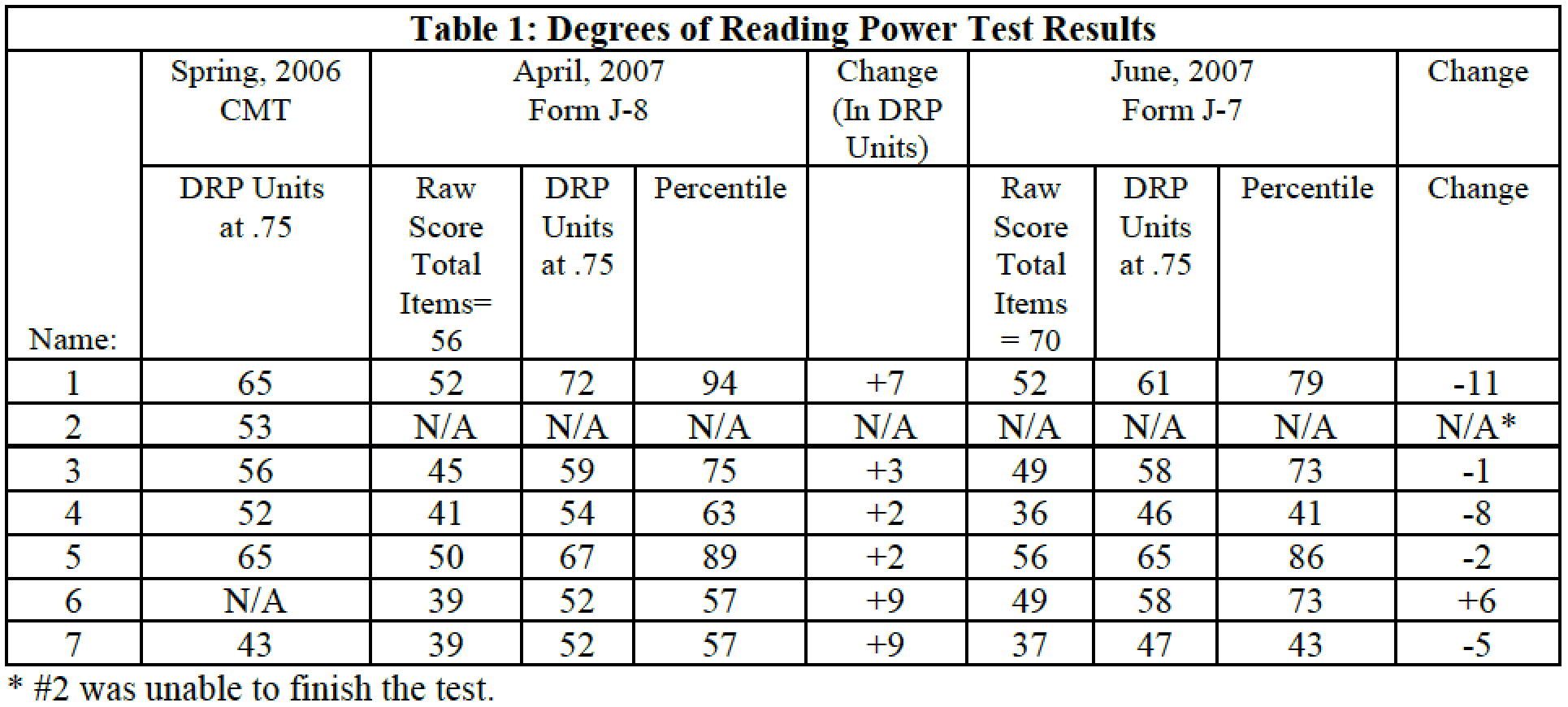

Six out of seven boys took a Degrees of Reading Power test, Form J-8, on April 25, 2007, which was shortly after the World War Two Club (Forbes Flying Tigers) meetings started. The seventh boy did not join the group until significantly after this test was administered. Another DRP Test, Form J-7, was given on June 12, 2007. Both tests were administered in my office with no interruptions. Directions were given just as they are in the administration of the DRP during the Connecticut Mastery Tests (CMT). The results from the CMT Degrees of Reading Power test for the spring of 2006, the DRP from April 2007, and the final test from June 2007 are reported in Table 1.

These DRP results indicate that these are a heterogeneous group. Their percentile scores for the April administration range from a high of 94 to a low of 57. These boys are capable readers, but according to their cluster teachers, do not perform up to their potential. When the scores are compared to the results from the CMT last spring, in each instance the scores increased. The increase ranged from a low of 2 points to a high of 9 points. These scores indicate that although there is capability, motivation may be the reason for the lack of daily higher-level performance. The boys did not perform well in June. The percentages ranged from a low of 41 to a high of 86. There was a greater point spread in the DRP unit scores: 46 to 65. The J-7 is a more challenging test and I believe several factors might account for the lower overall scores.

On June 1st, 2007, the MARSI was given to all seven participants. This easy-to-administer survey measures how often a reader uses appropriate strategies while reading. It consists of 30 statements that are rated on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means, “I never do this.” to 5 which is equivalent to “I always do this.”

Table 2: MARSI- Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory Results

Strategies

In order to insure consistency and accuracy, I read and clarified the statements. The surveys were handscored. The responses are grouped into three categories: Global Reading Strategies, Problem- Solving Strategies, and Support Reading Strategies. There is also an overall score. A score of 3.5 suggests that a reader uses this type of strategy often while reading. Low usage is 2.4 and under. The middle indicates that sometimes a type of strategy is employed, but its frequency is inconsistent. The following chart, Table 2, shows the results for all participants. In order to compare the results of the MARSI with the Degrees of Reading Power results, I created the following informational chart (Table 3). I used the following criteria to determine if there was a correlation: a score of 3.5 or above combined with a DRP score of 85 or greater would demonstrate a relationship that shows frequent use of reading strategies would result in proficient scores on the DRP. A correlation could also exist at the other end of the spectrum. A score of 2.4 or lower combined with a DRP score of below 50 would indicate that low use of reading strategies would lead to a deficient performance on the DRP. MARSI averages from 2.5 to 3.4 with DRP scores falling in the range of 51 to 84 would indicate that inconsistent use of reading strategies is indicative of an average DRP score. In four out if six cases, there was a correlation. The significance of using reading strategies does pay off in terms of increasing comprehension.

Table 3: Comparison of Results from the April DRP and MARSI

Qualitative

Attendance statistics illustrate an enthusiastic willingness to attend the Forbes’ Flying Tigers Club meetings. From mid-April until June 6th there were seventeen meetings. No one missed a meeting! On one occasion, I had to change a meeting from a Wednesday to Tuesday. Everyone remembered. There was one exception: one boy missed a meeting, due to the fact that he was on vacation the last week of May with his family in Florida.

Six out of seven of the boys returned their questionnaires. Table 4 below indicates how they responded to the question regarding what activities they would label as favorites.

Table 4: Favorite Reading Activities

All three hypotheses have been proven to have an impact on closing the literacy achievement gap for the boys in this study. Although this was a small sample, it represents a starting point. I believe that researchers were on target with their findings and that we need to continue to test them to verify what works and what doesn’t. We need to share this information with our colleagues and encourage and support their efforts on behalf of all students, but especially the boys. As mentioned several times throughout this paper, NCLB is having an impact on every public school classroom in the United States. The stakes are high. I wonder though, if too much time is being spent preparing students for these tests rather than on high quality instruction. Are we pumping in support services to those students who are just below goal at the expense of our struggling students and gifted students? Are we sacrificing our ability to teach based on current best practices as determined by the research, to teach a rigorous academic curriculum in order to achieve adequate yearly progress? These questions don’t have easy answers, but the future of our country is dependent on how we, as educators, answer them. After careful consideration of the research I did, I realize that although there is a very real gap in the literacy abilities of males, teachers do have some tactics that they can use. Freedmon, B. (2003) Boys and literacy: Why boys? Which boys? Why now? Paper presented at the 84th Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED477857. Gurian, M. & Stevens, K. (2005). The Minds of Boys Saving Our Sons from Falling Behind in School and Life. California: Jossey-Bass. King, K. & Gurian, M. (2006) With boys in mind/ Teaching to the minds of boys [Electronic version]. Educational Leadership, 64, 56-61. Smith, M.W. & Wilhelm, J.D. (2002). “Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys” Literacy in the Lives of Young Men. New Hampshire: Heinemann. Touchstone Applied Science Associates, Inc. (2002) Degrees of Reading Power Program Primary and Standard DRP Tests DRP Handbook J & K Test Forms. New York: TASA Literacy. Tyre, P. (2006, January 30). The trouble with boys. Newsweek, 44-52. United States Department of Education. (last modified 8/23/2003) Fact Sheet on the Major Provisions of the Conference Report to H.R. 1, the No Child Left Behind Act. Retrieved August 3, 2007, from http://www.ed.gov/print/nclb/overview/intro/factsheet.html.Summary

Implications for Education

Implications to Teaching and Learning

References