Laura J. Mead, Karen Burke, Lois Lanning, Jennifer F. Mitchell

Department of Education and Educational Psychology

Western Connecticut State University

Abstract

This study examined the impact of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies (self-regulating, creating meaningful connections, summarizing, and inferring) on comprehension and selfperception of struggling readers. The study also observed the relationship between the intervention and learning-style processing preferences.

The experimental research design utilized random assignment to group and used quantitative measures to explore the research questions. The 63 participants were identified as struggling readers at one elementary school in an urban school district.

There was a non-significant main effect for each dependent variable. The analyses also indicated no significant interaction between the two levels of the independent variable and students’ processing preference in relation to either dependent variable. Although no significant effects were realized, the experimental group performed as well as the control group on the cognitive measure. The significance of this finding supports the effectiveness of a newly implemented intervention for all types of learners. In light of SRBI and differentiation of instruction the findings support an effective intervention for global learners as well as analytic learners.

Introduction

Research consistently indicates that children who initially succeed in reading rarely regress. Those who fall behind tend to stay behind for the rest of their academic lives (Buly & Valencia, 2002; Burns, Griffin, & Snow, 1999; Juel, 1988; Valencia & Buly, 2004). “According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (U.S. Department of Education, 2006), 36% of fourth graders read below the basic level” (Torgesen et al., 2007, p.vii). There is a distinct need to provide explicit reading interventions to meet the needs of these struggling readers.

In the field of education the teaching of reading has been a subject of heated debate for decades. There has been little agreement with regard to the best approach to reading instruction. One theory proclaims a skills-based approach that emphasizes phonemic instruction will produce the best readers. Another theory argues that the only way students learn how to read is through a literature-based approach that has been associated with whole language. Recent literature has suggested that there can be a compromise between these two schools of thought (Baumann & Ivey, 1997; California Department of Education, 1996; Carbo, 2003; Frey, Lee, Tollefson, Pass, & Massengill, 2005; Honig, 1996; Pressley, 2006).

When the teaching of reading and writing is viewed in a holistic manner, the idea of balanced literacy instruction emerges. Balanced literacy is a comprehensive literacy approach that is not confined to a particular philosophy. Several of the components include but are not limited to reading and writing workshop, interactive reading and writing, read-alouds, accountable talk, and small group instruction. “It is an approach that requires and frees a teacher to be a reflective decision maker and to fine tune and modify what he or she is doing each day in order to meet the needs of each child” (Spiegel, 1998, p. 116). In addition to creating a model with an aspect of balanced components, a balance must be maintained between teacher-directed and learner-directed instruction, explicit and indirect instruction, whole group and small group interactions, and between authentic assessment, high-stakes assessment, and norm-referenced assessment (Au et al., 1997; Spiegel, 1998).

Balanced literacy instruction incorporates the various teaching strategies for skills and comprehension to best meet the needs of individual students. This literacy model permits the flexibility of instruction to address individual learning styles (Baumann & Ivey, 1997; Carbo, 2003). Varied instructional methods, grouping, and activities can better support all learning-style preferences (Dunn, Dunn, & Perrin, 1994). One of the most challenging aspects of balanced literacy is structuring an optimal 150-minute daily literacy block that is fluid and meaningful while incorporating each component effectively in a timely manner (Au, Carroll, & Scheu, 1997).

Struggling readers need more explicit instruction from a knowledgeable teacher to break through the cycle of reading failure. The 4 powerful strategies for struggling readers grades 3-8: Small group instruction that improves comprehension specifically target the following four comprehension strategies used in this investigation: self-regulation, creating meaningful connections, summarizing, and inferring (Lanning, 2009). Allington (2001) espouses to improve reading skills students must read extensively and frequently. The theory of selfefficacy and related studies indicate that with increased academic failures a student’s selfperception rapidly declines (Bandura 1977, 1997; Henk & Melnick, 1995; Schunk, 1984).

The review of research revealed a need for further empirical research to specifically address the comprehension deficits and self-perception of struggling readers in intermediate grades. Research also posited the necessity for alignment between student learning-style preferences and instructional methods. The contention of this research was to determine if the Four Powerful Strategies implemented through the gradual release lesson design (Duke & Pearson, 2002) had the potential to increase reading comprehension, address processing-style differences, and enhance students’ self-perception.

Method

This study examined the impact of the two levels of the independent variable, reading comprehension intervention instruction, (Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies/experimental group and no Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies/control group), on the two dependent variables, reading comprehension and reader selfperception of struggling readers in grades 3, 4, and 5. The moderator variable was learning-style processing preference (analytic or global).

Description of the Setting and the Subjects

Research was conducted at an urban school district in the northeast region of the United States. According to the US Bureau of the Census (2000), the socioeconomic background of the city’s population was low to middle class with a median home income of $53,664. The participating school was one of the most socioeconomically- challenged elementary schools in the district with 64% of the total student population eligible for free and reduced lunch. According to the 2007-2008 Strategic School Profile there was a total minority population of 69% and 58% of the total school population lived in homes where English was not the primary language. One full-time bilingual teacher and one full-time English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher provided services to 36% of the total student population ranging from kindergarten to fifth grade.

The target population was a group of students identified as struggling readers in grades 3, 4, and 5. The total population of struggling readers identified from one elementary school in the district comprised the 63 student participants in this sample. There were 11 staff members who participated in the study. Four staff members (three certified teachers and one instructional aide) were trained in the implementation of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies and the gradual release lesson design during two six-hour training sessions and monthly follow up professional development sessions throughout the course of the research. The four trained staff members provided instruction for the experimental group of students. Seven staff members (six certified teachers and one instructional aide) were not trained in the implementation of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies or the gradual release lesson design and conducted traditional small group instructional practices for the control group students.

Procedure

The researcher provided the four treatment instructors with two six-hour training sessions. The training included a copy of the book 4 powerful strategies for struggling readers grades 3-8: Small group instruction that improves comprehension (Lanning, 2009), a comprehensive resource binder, activities to review current research on strategy instruction and theoretical background related to the intervention, step-bystep process of the gradual release lesson design, and practice evaluating the teaching of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies using a gradual release lesson design. At the conclusion of each training session the participants provided feedback used to modify future professional development sessions for the entire group, small groups, and individuals. Follow-up professional development occurred at least monthly for the duration of the treatment.

The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies identifies the following four essential comprehension strategies: summarizing, creating meaningful connections, self-regulating, and inferring. Each strategy has an accompanying set of supporting skills, which often overlap (Lanning, 2009). The gradual release lesson design delineates Pearson and Gallagher’s (1983) gradual release of responsibility model into a step-by-step process in which teachers are able to plan deliberate instruction at each phase of the release.

In this process the teacher will:

- Give an explicit description of the strategy and when it should be used;

- Model the strategy in action;

- Collaboratively use the strategy in action;

- Guide practice using the strategy with gradual release of responsibility; and

- Allow the student independent use of the strategy (Duke & Pearson, 2002).

Trained teachers implemented the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies for 30 minutes a day, 4 times a week for 14 weeks. To ensure accurate implementation, the researcher monitored lessons using a tailored observation form (Lanning, 2009, pp. 143-148), provided written feedback, and conferred with each treatment teacher throughout the 14 weeks. Each teacher provided instruction for all four strategies and several skills over the course of the study. To track the strategies and skills covered, the teachers in the experimental group used the matrix from 4 Powerful Strategies for Struggling Readers Grades 3-8: Small Group Instruction that Improves Comprehension (Lanning, 2009, p. 8). The course of instruction and the order in which the strategies were taught varied from teacher to teacher based upon student need in each group.

Conversely, the focus for the control group students varied between each instructional group and the gradual release lesson design was not utilized as the method of instruction. However, students in the control group were exposed to similar conditions; small-group instruction that occurred 30 minutes daily, 4 times a week for the same14 weeks. Staff members who taught students in the control group were familiar with the materials and knowledgeable of the methods of instruction. Materials ranged from a variety of trade books to leveled commercial resources. Instruction for control group students was predominantly teacher-directed utilizing a calland- response method and isolated skills instruction.

Research touts explicit instruction and guided practice as the most effective methods to ensure comprehension (Duffy et al., 1987; Duke & Pearson, 2002, Palincsar & Brown, 1984; Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). Each lesson conducted using the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies intervention was predicated on the gradual release lesson design (Duke & Pearson, 2002). The design included explicit explanation and teaching of the strategy and underlying skill along with guided practice that allowed greater student responsibility. Guided practice provided the critical step to ensure appropriate use of each of the four strategies and the integration of strategies; the teacher provided corrective action and appropriate scaffolding techniques when observing students using each strategy in the small group. Students and teachers must be confident in their respective roles to best promote transfer of learning to a new situation (Bigge & Shermis, 2004).

Finally, data for the cognitive measure were collected using the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test (MacGinitie, MacGinitie, Maria, & Dreyer, 2000) for the achievement measure. The Reader Self-Perception Scale (RSPS) (Henk & Melnick, 1995) was used for the affective measure. RSPS pretest scores were analyzed to determine that there were no initial differences between group means. The Elementary Learning Style Assessment (Dunn, Rundle, & Burke, 2007) was administered to all student participants to identify each student’s learning-style processing preference (analytic and global) according to the Dunn and Dunn Learning-Styles Model.

Learning-Style Processing Preference

This investigation was concerned with the psychological processing styles of global and analytic as determined by the Elementary Learning Style Assessment. A learner who prefers information presented in an anecdotal manner that initially imparts the “big picture” through stories that can be self-related characterizes the global processing style. Global learners generally prefer to work with a small group in an informal setting with low light. A learner who prefers a step-bystep methodology with specific grading criteria and concise feedback, characterizes the analytic processing style. The analytic learner usually prefers to work alone in a formal setting with bright light. An integrated processing style indicates that a learner utilizes both types of reasoning (Burke, 2003).

Description of the Research Design

The experimental research design utilized a stratified random assignment to form the two groups (experimental and control) and used quantitative measures to explore the research questions using an equivalent group design for both dependent variables. The independent variable was reading comprehension intervention instruction with two levels: (a) students who received instruction using the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies and (b) students who did not receive instruction using the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies. The moderator variable was learning-style processing preference. The two dependent variables were reading comprehension achievement and reader self-perception.

Results

Two-way ANOVAs (p ≤ .025) were conducted to determine a main effect for group (experimental and control) for each dependent variable. Data also were analyzed to determine an interaction effect between the independent variable and processing-preference in relation to each of the dependent variables.

These statistical procedures determined there was a non-significant main effect between group means of the experimental group (M = 467.97, SD = 26.19) and the control group (M = 469.58, SD = 25.44) for reading comprehension F(1, 56) = .068, p = .795, η2 = .001. Also, there was no significant difference between group means of the experimental group (M = 121.48, SD = 16.18) and the control group (M = 113.52, SD = 15.832) for the affective dependent variable (reader self-perception) F(1, 56) = 2.119, p = .151, η2 = .036. In addition, the results indicated no significant interaction between the two independent variables in relation to either of the cognitive F(1, 50) = .012, p = .914, η2 = .000 or affective F(1, 56) = 2.119, p = .151, η2 = .036 variables. The statistic indicated that global or analytic learners did not perform differently when exposed to either the experimental or control conditions. Although the analyses indicated no statistical significant differences, Table 1 and Table 2 show the mean scores for experimental students identified as having a global processing preference were higher than the experimental students identified as having an analytic processing preference for both the cognitive and affective measures. This finding illustrated the positive impact that the experimental intervention had on global learners.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Comprehension Extended Scale Scores

Analytic

Global

462.30

469.06

28.308

28.410

10

16

Analytic

Global

466.08

474.47

27.506

24.991

13

15

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Reader Self-Perception Scale Posttest Scores

Analytic

Global

114.40

125.25

17.646

15.652

10

16

Analytic

Global

113.31

113.40

15.440

14.975

13

15

Discussion

The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies (self-regulation, creating meaningful connections, summarizing, and inferring) used as an intervention exemplified the ideology of Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development and teaching for transfer (Bigge & Shermis, 2004; Marini & Genereux, 1995). This study supported the assertion that the explicit instruction of a few powerful comprehension strategies, in a gradual release lesson design, would promote transfer of strategy use to new learning situations. The results indicated that the experimental intervention was equally effective for all learners and as effective as the alternative instructional methods.

Implications

This study provided support for the implementation of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies within a balanced literacy model as an effective intervention for students in grades 3, 4, and 5. The findings represented by the data showed no significant difference in mean scores, but suggested that students who received the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies performed as well as and in the case of integrated learners better on the cognitive measure than their control group counterparts. The findings also indicated the experimental conditions were equally effective for all processing preferences; experimental students identified with global and integrated processing preferences scored slightly higher than students identified with an analytic processing preference. This finding is of interest because a majority of elementary students exhibit a global learning style, but are frequently taught in an analytic manner. The data showed similar findings for the affective measure; global students in the experimental group scored the highest overall score on the Reader Self-Perception Scale.

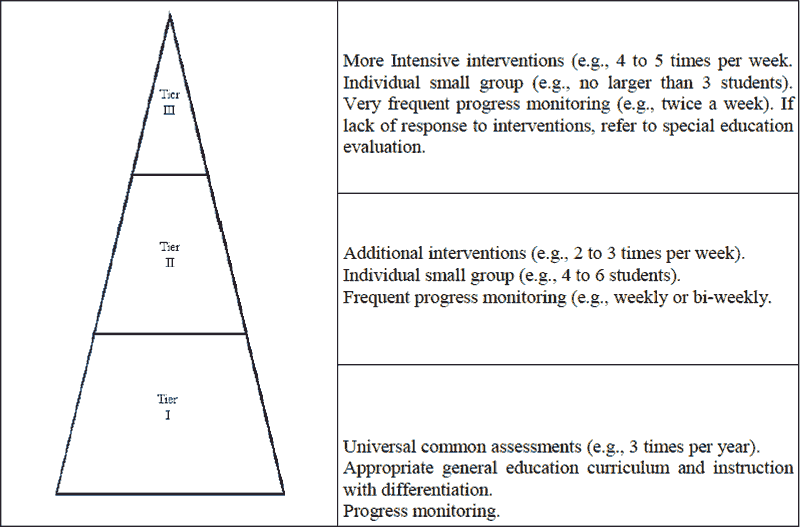

Response to Intervention

In light of Response to Intervention (RTI), districts nationwide are striving to provide staff with research-based interventions that are manageable to implement and cost-effective. All aspects of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies are research based (Duke & Pearson, 2002; Lanning, 2009; Pressley, 2006). Professional development can be site-based utilizing resident experts in comprehension instruction. The parameters of the instruction (30 minutes a day, 4 times a week) coincide with RTI expectations. The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies intervention is not curriculum specific and would complement individual district’s curriculum, materials, and resources. The flexibility of the instruction allows teachers to engage students by choosing a variety of texts of high interest and motivation.

Strategy Instruction for All Texts

The National Reading Panel (NICHHD, 2000) has suggested the need for strategy instruction that is effective for both narrative and expository texts. The strategies and skills presented in the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies are appropriate for either narrative or expository texts and a variety of genres. The National Reading Panel (NICHHD, 2000) also advocated for a variety of procedures to instruct educators in how to use effective comprehension strategies. The step-by-step process of the gradual release lesson design is a critical component for teaching comprehension. Also, it is imperative for teachers to have a comprehensive understanding of the terms strategy and skill. A strategy is a systematic plan consciously adapted and monitored to improve one’s performance in learning (Harris & Hodges, 1995). A skill refers to the parts of acts that are primarily intellectual (Harris & Hodges, 1995). The gradual release lesson design and the discrete teaching of strategies and skills are the mainstay of the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies intervention.

Core Programs Versus Supplemental Support

Dewitz, Jones and Leahy, (2009) informed schools and districts of significant gaps for a multitude of learners in commercially purchased core programs. Many schools use core programs as the sole vehicle for literacy instruction. However, in each of the reviewed core programs, strategy instruction was evaluated as having breadth but not depth. The core programs were viewed as particularly detrimental to struggling readers; over 51 disconnected skills and strategies were coded for five different programs, the terms strategy and skill were often used interchangeably, and there was little to no guided practice or release of responsibility to the student.

The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies provides supplemental instruction to support struggling readers with explicit instruction using a variety of texts and genres. A noticeable overlap exists in each of the four strategies because comprehension is often attained through many of the same skill sets for the use of the various strategies. Therefore, it is critical for students to understand the difference between strategies and skills, when and how they are used, and that the same skills can be applied with a different focus for each strategy. Lanning’s (2009) book, 4 Powerful Strategies for Struggling Readers Grades 3-8: Small Group Instruction that Improves Comprehension, provides distinct definitions for each term. The definitions of strategies and skills are supported and modeled throughout the book. In addition, the professional development sessions throughout this study continually emphasized the importance of the distinction between these two terms and how to effectively communicate the difference to students.

Implementation Dip

A critical implication of which researchers and practitioners should be cognizant is the implementation dip of a new intervention. Michael Fullen described the implementation dip as “a dip in performance and confidence as one encounters an innovation that requires new skills and new understandings” (2001, p. 124). There are two significant problems faced during a change such as learning a new instructional method: (a) the social-psychological fear of the change itself, and (b) not knowing how to use the new method well enough to make the change work (Fullen, 2001). Adult participants teaching the experimental group expressed these concerns. However, the school was engaged in a process of transformation and viewed the study as an opportunity for professional growth. Using the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies as an intervention tool for the first time required developing new pedagogical skills for instruction and a new understanding of the comprehension process. The implementation dip may explain the cognitive results for the experimental group. Nevertheless, the experimental group performed as well as, and in some cases better than, students in the control group.

Fullen’s ideas were realized in this study when the teachers and principal of a second school that had initially been part of the investigation distinctly expressed the social-psychological fear of change. Ultimately the school withdrew from the study.

Embedded Professional Development

Finally, the individualized and embedded professional development provided the experimental teaching staff with a new pedagogical foundation. The four adult participants who taught the students in the experimental group received intensive short-term training. Professional development sessions based upon the needs of the adult learners were scheduled throughout the 14- week treatment. The results indicated that in a relatively short period of time, the newly introduced intervention was as effective as the traditional instructional strategies that were routine to staff and students. Although no statistical significant difference was realized, the students in the experimental group performed as well as, and in some cases better than, students in the control group. This finding is especially encouraging when considering that strategy instruction “is extremely time intensive, with effects often taking months to occur” (Dole et al., 1996, p. 66).

Summary

This study coupled the theoretical foundations for effective strategy instruction with a practical approach to implement an effective intervention. The data yielded results that indicated the treatment was an effective instructional approach for a variety of learning styles and supported reader self-perceptions. Although no statistical significance was realized, students who received instruction using the experimental intervention scored as well as and in some cases better than students who received alternative methods of reading intervention. This is a substantial finding because the alternative instructional methods were familiar practices historically implemented by teachers to promote comprehension in the upper elementary grades. The fact that the Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies was a new intervention implemented over a 14-week period and had an immediate impact showed promise for continued use and refinement. In addition, all teachers trained in the process expressed the benefits that they believed students yielded that the data did not measure. Many of the students in the experimental group began asking thought-provoking questions and engaging in conversation about the texts with one another without being prompted as the treatment progressed.

Instruction is often delivered in an analytic step-by-step method. It is imperative to find interventions for struggling readers that appeal to all types of learning styles. The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies instructional practices were conducive to both global and analytic learning styles. The intervention yielded positive results for students who exhibited a global and integrated learning style. Global and integrated learners often need a “big picture” view or holistic manner of instruction. The emphasis on creating meaningful connections and inferring through extensive conversations between students to grasp the meaning of the text at a deeper level was advantageous for the global and integrated learners. Global learners in the experimental group also exhibited a more positive selfperception of themselves at the conclusion of the investigation.

A wealth of information exists on reading comprehension instruction. A variety of authors have provided lists and the theoretical principles on which the lists are founded. Questions remain about which strategies work best, in what combination, and for whom. The Four Powerful Comprehension Strategies used in this study provided a step toward creating practical application information combining a variety of research-based practices.

References

Allington, R. (2001). What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-based programs. Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley Longman.

Au, K., Carroll, J., & Scheu, J. (1997). Balanced literacy instruction: A teacher’s resource book. Norwood, NJ: Christopher Gordon.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

Baumann, J., & Ivey, G. (1997). Delicate balances: Striving for curricular and instructional equilibriums in a second-grade literature/strategy-based classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 32(3), 244-275.

Bigge, M. L., & Shermis, S. S. (2004). Learning theories for teachers (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Buly, M., & Valencia, S. (2002). Below the bar: Profiles of students who fail state reading assessments. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(3), 219-239.

Burke, K. (2003). Research on processing style: Step-by-step toward a broader perspective. In R. Dunn & S. Griggs (Eds.), Synthesis of the Dunn and Dunn learning-style model research: Who, what, when, where, and so what? (pp. 45-47), Jamaica, NY: St. John’s University.

Burns, M. S., Griffin, P., & Snow, C. E. (Eds.). (1999). Starting out right: A guide to promoting children’s reading success. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

California Department of Education (1996). Teaching reading: A balanced comprehensive approach to teaching reading in prekindergarten through grade three. (Reading Program Advisory Publication No. 95812-0271). Sacramento, CA: Author.

Carbo, M. (2003). Achieving with struggling readers. Principal, 83(2), 20-24.

Dewitz, P., Jones, J., & Leahy, S. (2009). Comprehension strategy instruction in core reading programs. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(2), 102-126.

Dole, J. A., Brown, K. J., & Trathen, W. (1996). The effects of strategy instruction on the comprehension performance of at-risk students. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(1), 62-88.

Duffy, G. G., Roehler, L. R., Sivan, E., Rackliffe, G., Book, C., Meloth, M., & Bassiri, D. (1987). Effects of explaining the reasoning associated with using reading strategies. Reading Research Quarterly, 22, 347-368.

Duke, N., & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A.E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 205- 242). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Dunn, R., Dunn, K., & Perrin, J. (1994). Teaching young children through their individual learning styles: Practical approaches for grades k-2. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Dunn, R., Rundle, S. M., & Burke, K. (2007). Elementary learning styles assessment: Research and implementation manual. Retrieved January 20, 2010 from www.learningstyles.net.

Frey, B., Lee, S., Tollefson, N., Pass, L., & Massengill, D. (2005). Balanced literacy in an urban school district. Journal of Educational Research, 98(5), 272-280.

Fullen, M. (2001). Leading in a culture of change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Henk, W. A., & Melnick, S. A. (1995). The reader self-perception scale (RSPS): A new tool for measuring how children feel about themselves as readers. The Reading Teacher, 48(6), 470-482.

Honig, W. (1996). Teaching our children to read: The role of skills in a comprehensive reading program. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 437-447.

Lanning, L. (2009). 4 powerful strategies for struggling readers grades 3-8: Small group instruction that improves comprehension. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

MacGinitie, W. H., MacGinitie, R. K., Maria, K., & Dreyer, L. G. (2000). Gates-MacGinitie reading tests: Directions for administration (4th ed.). New York, NY: Riverside Publishing.

Marini, A., & Genereux, R. (1995). The challenge of teaching for transfer. In A. McKeough, J. Lupart, & A. Marini (Eds.), Teaching for transfer: Fostering generalization in learning (pp. 1-19). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHHD). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Retrieved September 20, 2009 from Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Palincsar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehensionfostering and monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1, 117-175.

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317-344.

Pressley, M. (2006). Reading instruction that works: The case for balanced teaching (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Schunk, D. H. (1984). Sequential attributional feedback and children’s achievement behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 1159-1169.

Strategic School Profile, 2007-2008 for the Danbury Public School District. Connecticut State Department of Education. Hartford, CT. Retrieved January 20, 2010 from http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/site/default.asp.

Torgesen, J., Schirm, A., Castner, L., Vartivarian, S., Mansfield, W., Myers, D., & Haan, C. (2007). National assessment of title I: Final report: Volume II: Closing the reading gap: Findings from a randomized trial of four reading interventions for striving readers (NCEE 2008-4013). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved May 15, 2009 from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pdf/20084013.pdf.

Valencia, S. W., & Buly, M. R. (2004). Behind test scores: What struggling readers really need. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 520-531.

U. S. Bureau of the Census. (2000). Census report. Retrieved August 20, 2009 from http://www.ct.gov/ecd/cwp/view.asp?A=1106&Q=250616

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds. & Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.